- Home

- Spurrier, Ralph

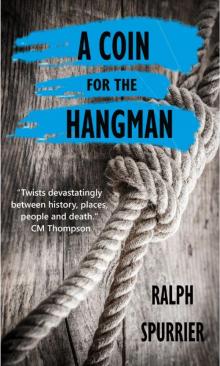

A Coin for the Hangman

A Coin for the Hangman Read online

A Coin for the Hangman

Hookline Books

Booksellers never know what they might find in an estate sale. When our man finds the tools of England’s last hangman, along with the diary of a condemned man he executed – a diary that points the finger in a disturbing direction - he knows he has a mystery to solve. Was there a miscarriage of justice? Did the wrong man die at the noose? And just who is telling the truth?

For here the lover and killer are mingled

who had one body and one heart.

And death who had the soldier singled

has done the lover mortal hurt.

(Keith Douglas: Vergissmeinicht.)

A bird does not sing because it has an answer.

It sings because it has a song.

(Chinese proverb)

For

VHS and MMS

Because I never knew and never asked.

It was the photograph that did it for them. All three of them. A simple square portrait photograph probably no bigger than three inches by two which would fit neatly into an army tunic breast pocket or, as I was to discover much later, secreted in the back of a German mantle clock. It was the photograph of a young woman named Steffi – her surname now lost forever – aged probably about eighteen or nineteen, her blonde hair braided neatly around her head and uncertainly smiling as if her mother, standing behind the photographer, had urged her to show her teeth for the camera. There was nothing particularly unusual about the photograph; it was just like thousands of others that girlfriends gave to their soldiers as they left for the fighting at the start of the Second World War. Germans, Italians, British, they would all tuck the photographs away in their wallets or tunic pockets, touch them for good luck, bring them out at camps and billets just to peer at fondly or to show off to their mates. Many of these men were to die in the mud or the desert with the photographs fading along with their rotting flesh and disintegrating uniform, the smiling faces of their girlfriends and wives fading into oblivion while those same women back home wept tears and suffered heartache as they wondered if their men were ever to return. This particular photograph escaped that fate, however, being rescued from the dead body of a German tank commander in the North African desert, and was passed from hand to hand until it fell, quite unexpectedly and, as we shall see, with unforeseen tragic consequences, from the back of a mantle clock ransacked from a house in Bavaria. My research was to uncover that this little, innocent photograph passed through the hands of at least five people, all of whom were to die violently. The irony was that for all my research and effort over the years I never once saw that photograph and have no real idea where it now might be or even if it still exists. The story begins back in 1987 and, like most opportunities in my line of business, it came completely out of the blue with a simple phone call.

“Hello Ralph. You still mucking about with books?” The voice at the end of the line was vaguely familiar but not one I had heard for some years. The inference that my book-dealing business was less than a proper means of earning a living immediately put me on guard, and although it was a commonplace attitude it still managed to rile me whenever I found myself explaining the economics of buying and selling books.

I was desperately trying to place a name to the voice on the end of the phone as I replied, “Yes, still surrounded by books.” I laughed deprecatingly. “And even selling one or two occasionally.”

“Good. Good.” The recognition remained stubbornly locked away in the back of my memory. “Look. I have a little business I can put your way if you’re interested. I’m acting as executor for one of my clients. Well, it’s a late client, actually.” He laughed, and in that moment I suddenly recognized the voice of a solicitor I had dealt with some ten years ago when moving house. I was amazed he had remembered me. “The fellow has no offspring or living relatives as far as we’ve ascertained, and the trouble is that he was living in rented accommodation and the landlord is keen to relet the property. The place is stuffed with furniture and books. A lot of books apparently.”

Mentally, I assessed the bank balance and the space left in the store-room. Both were pretty tight and I wasn’t looking to spend much on new stock. But the lure of a collection of books always won out and I felt I could always say “no” if they turned out to be worthless.

The solicitor’s voice carried on: “The furniture we’ve managed to sort out – never much to be made on that kind of stuff anyway – but I felt there might be some mileage in the books. Interested?”

“Yes, sure.” I wanted to sound professional but I knew that nine times out of ten these kinds of calls were a complete waste of time. “Happy to take a look for you and let you know if I can use them. I’m assuming they’re reasonably local and not in the Shetland Isles?”

I had unhappy memories of the promise of a big book collection in Belfast that I had flown out to view at the height of the Troubles – that’s how bibliomania gets you – only to discover that the library was housed in an old coal store and had been gradually rotting away for several years. It took me no more than twenty seconds to make an assessment of 5,000 books. The fellow who had invited me over to view the library was more than a little surprised when I suggested he hire ten skips and lob the whole lot into landfill. The ride back to the airport had been in a difficult silence. I vowed never to go on a long-distance wild-goose chase again.

“East Dean, just this side of Eastbourne. About half an hour’s drive. That OK?”

“Yes, that’s fine.” I thought that I could at least combine it with a trip to the Eastbourne second-hand bookshops which still unearthed some rarities from the ageing and retired population in the area. We finalized the arrangements – I was to meet the agent at the house – and then get back to the solicitor if there was anything worth salvaging.

Despite many years of book dealing, the sense of expectation on walking in on a fabulous collection never diminishes, even though 99 times out of 100 the reality is somewhat different. I had been in any number of houses, viewed the paltry offerings of a shelf of dog-eared paperbacks or faux leather book club editions that the owner had never read but had kept buying on a monthly basis, cupboards that had disgorged out-of-date encyclopaedias, cookery and gardening books and suitcases that opened to reveal browned and crumbling souvenir newspapers of the Queen’s Coronation. I had learnt to live with the look of supreme disappointment on the face of the proud owners when I turned such offerings down. Still, to have first pickings on a large collection never failed to set the pulse racing and I set off for the East Dean address the next day. I met the fresh-faced boy from the estate agency by the front door of a bungalow that had seen better days and together we went in to the front room.

“I was all for chucking this lot out with the furniture but your solicitor friend said there was some stipulation in the will that the books had to be kept together and sold as one lot.” He pointed towards the large piles of books that now sat on virtually every square foot of floor space, waving his hands over the stacks as if he were a magician hoping they would disappear. “Bit of a nuisance, I have to say. Could do with someone taking them away pretty smartish.”

He raised a questioning eyebrow at me. I’d been in the business long enough to recognize someone who would be prepared to take anything just to get the stuff off his hands. Since this fellow was only the agent and the solicitor knew bugger-all about books, I sensed an opportunity to increase my stock of books for a very minimal outlay. I prayed that there would be just one gem amongst the collection, just one that would provide a comfortable buffer of cash for the next few months.

However my first visual skirmish didn’t give me much enthusiasm. Horse-racing annuals, woodworking books, a run of Penguin crim

e titles in their distinctive green and white covers, a guide book to Durham, an ABC railway timetable – seemingly there was little here to get excited about. Getting down on my hands and knees, I craned my neck to read the titles lying on their sides. It was an eclectic mix of novels, poetry and philosophy, mixed in with the more mundane, including, for my own interest, a number of books on criminal trials. Whoever had owned these books had a wide, varied and unusual taste. There were enough crime fiction books in the collection, including a nice little run of war-time Agatha Christies, to make it just about worth my while. I made a quick decision.

“OK. I’ll take the lot away for you.”

The look of delight on the agent’s face was immediate. “Today? Now?”

I looked around the room and reckoned I could just about squeeze the lot into the back of the Volvo Estate if I folded the back seats down. I nodded. “Yes, shouldn’t be a problem. I presume I negotiate the price with the solicitor?”

“Nothing to do with me. Just pleased to see the back of them.”

Together we loaded them all into the back of the car. In any collection of books there are always what I call the bits and pieces, the flotsam and jetsam. Theatre programmes, cuttings, pamphlets, magazines, fold-out maps – things that don’t fit easily onto shelves and which normally accumulate in sideboards or get tucked away in boxes. There was one such box with this collection and I dumped it on top of the stacks of books and drove away back to my store-room.

The next day I began to take a closer look at what I had bought. I have always been fascinated by people’s books collections and, as any bibliophile will attest, there is a lot one can deduce about a person by the books they own. This time, however, I was puzzled by the enormously diverse nature of the subjects and, put all together, they just didn’t add up. I sorted them out into rough categories. The paperbacks I put on five shelves with the green and white Penguins forming the bulk of the titles. Next came the practical stuff – the previous owner had obviously been a keen woodworker at one time. Two shelves of horse-racing guides, bloodstock manuals and books on betting told me he had been more than an occasional visitor to the race courses around the country. I reckoned I could offload those fairly quickly to a specialist equine book dealer I knew.

Next was what I classed as the “literary” stuff: James Joyce, H.G. Wells and George Orwell, with collections of poetry by Yeats, Owen and Manley Hopkins. And there on its own, just one children’s book – a fairly well-worn copy of Madeline by Ludwig Bemelmans. Then finally, a row of biographies, autobiographies and other material all related to crime, trials and executions. I’d always had a gruesome fascination with the whole panoply of capital punishment and had already earmarked a few of these to go into my own collection.

By chance, I picked out the autobiography of Albert Pierrepoint, the most renowned British hangman of the twentieth century. Opening up the book I was startled to find a hand-written inscription on the front endpaper – apparently from the author. It had been crossed over in red pen but was still clearly visible underneath.

To Reg, my partner “in crime” – who almost let one “bird” fly away!

Underneath the inscription was a crudely drawn gallows with a body swinging from the rope. Appalled and fascinated, I stared at the handwriting and the big red cross that slashed right over the page. Just who had owned these books? I remembered the agent telling me that his client’s will had insisted that the books be sold in one lot and not to be broken up. Why? That was just the question I asked the solicitor the next day when I phoned to tell him I had collected the books. He was unable to expand on the will’s stipulation.

“We see this kind of thing from time to time and it remains a mystery both to us and the legatees. Some bee in the late client’s bonnet I suppose, but most times that bee expires along with the client.” His laugh betrayed a sense of wonder at the occasional stupid request in his clients’ wills.

I laughed sympathetically and proceeded to mention a low figure I’d be happy to pay for the books. As they were already in my stock room I knew the solicitor had little choice but to accept my offer, although it didn’t stop him trying to squeeze an extra fifty quid out of me. I said I’d be happy to bring all the books round to his office and leave them with him if he thought the price was too low. The deal was quickly completed, but I had one last question:

“Your client. What was his name? Just between you and me.”

I could sense more than a little hesitancy at the end of the line.

“Just between you and me?”

I agreed.

“Reginald Manley.” The name rang faint bells but I couldn’t make a connection.

“Why would I have heard of him?”

Again, that hesitation. “Not many people would remember him, but someone like you, with your specialization in crime, should recall the name.” He gave a nervous laugh. “Reginald Manley was one of the last public hangmen.”

I put the phone down and turned to look at the books on the shelves. I was staring at the personal library of a man who had executed people for a living.

It took me some time to tease out the information on Reginald Manley. Bearing in mind that these were the days before instant access at the touch of a computer button or internet search, I had to resort to the library and newspaper archives to get most of the background. It seemed he had been first employed by the Home Office shortly after the Second World War to be an assistant hangman and he had certainly worked with Pierrepoint on a number of occasions. So the inscription in the Pierrepoint book looked genuine. Mentally, I added a hundred quid to the asking price of the book. Around 1951 he was promoted to be principal hangman and had acquired his own assistant – one Jim Lees. Then, for no apparent reason, the name of Reginald Manley dropped out of the archives sometime after May 1953. The solicitor had told me that Manley had been about eighty-seven when he died so he was as old as the century and had therefore, presumably, retired at fifty-three. I didn’t know to what age hangmen were employed – perhaps fifty-three was old enough to hang up the rope as it were – but I kept recalling Pierrepoint’s inscription in his autobiography. Was it some kind of in-joke or was Pierrepoint referring to a particular event?

Returning to my book room one day shortly afterwards, I noticed the box of ephemera I had taken from Reg Manley’s house. Lifting off the lid, I peered at the mound of paper inside. It certainly didn’t look very promising. London Transport bus maps, betting slips, receipts – the fellow obviously hadn’t thrown anything away. There were a couple of strange leather straps with buckles – much too short to be trouser belts – and what was once a white bag but now faded to a grubby grey, with drawstrings at the opening. Half-way down the box I came upon something much more substantial, a limp, black-covered book, devoid of any title or author name. Opening the book, I could see it contained about forty or fifty pages of neat handwriting in pencil which began on the very first page. I sat back on the floor and read the opening sentences and felt a dense, cold fear creep over me.

I don’t know who you are and, probably, you don’t know who I am. Yet. But in three weeks you will come to this room to kill me. To this little grey cell with your ropes and buckles and apparatus, your wicked skills, and you will kill me. You will bind my hands and feet and you will cover my eyes. And then you will drop me from this daylight into oblivion. A brightness falling from the air; this fat Icarus, crashing to earth. I have a story to tell. Will you ever believe it and what will you do when you have read the truth?

It took me about two hours to read the whole text. The handwriting, neat to start with, became erratic the further I read and the last pages were very difficult to decipher. Some words or phrases were indistinct and I had to make educated guesses at their meaning, but by the time I had reached the last page I knew what I had in my hand. It was the diary of the last three weeks in the life of a condemned man, one Henry Eastman – and it was personally addressed to Reg Manley, the man I presumed had carried out h

is execution. I went to the notes I had made at the library and saw that the very last execution that Reg Manley had been employed on was in May 1953 and the name of that man was indeed Henry Eastman. I went back to the box and saw the leather buckles and the bag with the drawstrings and suddenly, with a sick lurch in the stomach, I knew exactly what they were.

For the next three weeks I read and reread the diary. The phone rang unanswered, letters and orders lay fallow on the hall table, food was taken only when hunger overtook my intense curiosity. There was something extraordinary and exceptional about the language. Henry Eastman was only twenty-four when he was hanged for murder, but the style and competence of the text was that of a man twice his age. Phrases and words he used looked familiar from other contexts but I couldn’t immediately place them. Although, as a bookseller, I specialized in true crime and detective fiction, I had read widely in many other areas of literature over the years and I was sure I had come across some of the phrases Henry had used. I began to make notes as I read and reread the diary, struggling over some of the final pages, but eventually deciphering every last word. There were quotes and references strewn throughout the whole text and whenever I suspected a direct or indirect quote I added it to the growing list. By the time I had finished I had filled two whole foolscap pages and I was sure that I had probably missed as many more. I looked at my notes and the quotes and wondered where the key to all this lay. It took me over a week to spot the first clue which, in turn, began to unlock some of the other secrets the diary held.

It came from a section of the diary in which he was writing about a young girl called Madeleine that he knew at the age of ten in the year just before the Second World War. They had formed a close attachment which he had described as “too deep for taint.” Where had I read or heard that phrase before? I racked my brains for days trying to locate the quote but nothing would come to mind. It was late one evening with the rain rattling against the window and the wind shredding the last leaves from the autumn trees that the answer came to me. I was sure I remembered it from a Wilfred Owen poem. I didn’t have a copy of his poetry on my own shelves but I knew where there was one – in the Reg Manley collection that was sitting on the sorting shelves in the book room downstairs.

A Coin for the Hangman

A Coin for the Hangman