- Home

- Spurrier, Ralph

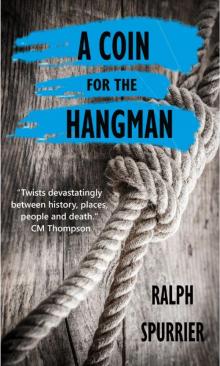

A Coin for the Hangman Page 3

A Coin for the Hangman Read online

Page 3

Bernhard tucked the photo into the breast pocket, shook his father’s hand and picked up his suitcase. With an assured step and a quick glance back towards the station, he boarded the little train. His father took another look at his watch and then signalled to the driver who was looking back from the window of the engine cab. A short billow of smoke blew from the stack, followed by a sharp whistle, and the engine with its tail of four carriages slowly moved forward, warily crossing over the points at the end of the platform. Herr Vogel turned back towards the station office and caught sight of Steffi standing by the rear of building, shadowed by the surrounding trees. He was never to tell his wife of the chill that ran through him at that moment, the sudden inexplicable draining of confidence and the terrible thought that perhaps he may never see Bernhard again. Quickly, he turned his head and looked towards the train as if hoping that it might have stopped, but the last carriage was just disappearing around the wooded bend and then it was gone. Stepping on to the tracks, he placed his foot on the shining metal line. He could feel the trembling in the strip that led away into the wood and he stood there in the morning sun, with the sound of a blackbird pinking a warning of some unseen danger in the nearby trees, until the very last traces of the train’s existence had disappeared and the drifting smoke from the engine melted into the bright blue of the sky and was gone.

Monday, May 11th 1953

Reg Manley

Reginald Manley lay next to his still sleeping wife and casually calculated the distance from the nape of her neck as it lay on the pillow to the point between the second and third vertebrae, that sweet spot, the dislocation of which would kill her almost instantly. The early morning light that filtered through the net curtains was just strong enough for Reg to see as he suspended his hand warily over the back of her neck, spanning the distance between thumb and forefinger from the cortex of her brain and the point at which disconnection would turn out the light. A life extinguished so easily with just one simple wrench.

He turned to lie on his back, peering sideways as he did so to check the time on the travel clock that perched in its case by his side of the bed. 6.15 am. An hour and a quarter before he had to get out of bed. He sighed. He was waking earlier and earlier these days, partly because Doris refused to have the heavy curtains closed at night – “it’s as dark as laying in your coffin with them closed” – and the nets did little to keep out the morning light. But partly he was beginning to realize that at the age of fifty-two he was reaching a turning point in life which increasingly unsettled him although, as yet, he was unable or, in truth, unwilling to identify the exact cause. This wasn’t where he planned to be at this time of life, but then any hopes and ideas that he might have had were thrown out the window fourteen years before in 1939 with the arrival of his call-up papers. Reg had made a conscious effort to erase the memories of those war years and had only ever spoken about them in the most general of terms to Doris. But on mornings like this, when sleep evaded him, the memories rose up unbidden. He quickly brought his hand to his mouth and bit into the fleshy part between thumb and forefinger, inflicting pain in an attempt to banish the ghosts, but still they refused to disappear completely. The image of an emaciated woman, toothless and filthy in rags, reaching out towards his hand brought a sweat to his brow and made him suddenly sit up in bed. Beside him, his wife stirred. Reg watched as Doris twisted a little to adjust her pillow slightly, but she remained with her back turned towards him. He settled back slowly on his pillow in a half-sitting position and reached for the book which he kept on his bedside cabinet. Agatha Christie’s They Do It With Mirrors had been the Christmas present from his wife the year before but he had only just started it. He had a long run of Christie novels – all of them gifts from his wife who, without fail, had presented him with one every year since they were married. She had even saved up the ones that were published during the war while he was away and, on his first night back after his eventual demob, had proudly pushed the packet of ten books across the kitchen table. They were easy reading, and there was no doubt the author was clever with plot twists, but Reg found lately that the stories were becoming laboured. This one, set in a country house converted to a borstal, had his head spinning with the number of characters who were related in all kinds of ways, but he would probably persevere to the bitter end if only just to find out whodunit.

At 7.30 am the alarm went off. Reg closed the book shut and swung his legs over the side of the bed. As usual, almost like an automaton, his wife did the same on her side. Without speaking, she gathered her dressing gown from the hook on the back of the door and went downstairs to get breakfast ready. Doris always argued that she wasn’t a “morning” person, but Reg knew that the almost total silence between them from rising to the moment he went out the door to work was a token of something more troubling.

Partially dressing before shaving, Reg stood at the bathroom mirror in his vest with the braces of his suit trousers hanging loosely from his waistband. Lathering the shaving brush, he lifted it to his face. Today, however, he hesitated, the soapy froth running down the wooden handle of the brush and onto the nicotine-stained ends of his fingers. Perhaps now, for the very first time, he noticed his father looking back at him from the mirror. The same hair, thinning at the temple, brushed straight back, and there was more than a hint of grey around the ears. He ruffled the hair with the tips of his fingers and peered closely at the reflection, twisting his head from left to right, unsure if he could detect how far the flecks of white had spread. He pulled his hand down over his cheek and neck, feeling the dark stubble under his chin. A hint of a jowl softened the once sharply defined chin. The pinch of the spectacles that he now used permanently for his figure work had left noticeable impressions on the sides of his nose, and the skin under his eyes looked darker. Quickly lathering his cheeks and upper neck, leaving the moustache clear to the edges of his mouth, he stropped the Darwin razor a few times with a firm thwick-thwack, thwick-thwack, before applying the edge just below the ear and scraping downwards on one cheek towards the chin. Flicking the shaved soap and cut bristle from the razor into the sink, he repeated the movement on the other cheek, bringing his hand down in a smooth curve while pushing his nose to one side with the thumb of his other hand.

The sound of rain on the bathroom window made him pause and he turned towards the net curtain. He drew it aside with the head of the razor, leaving a trace of lather on the edge of the net. Peering out through the rain-streaked glass, he scanned the sky with its heavy grey clouds hovering just above the ossified forest of factory chimneys that sprawled away into the murk. From the nearest chimney a sickly drizzle of brown smoke leaked and bled into the sky. It was adorned with the name of the abattoir – MARTIN – which, when new, had blazoned out in clear white paint and was visible for miles around. Now it had all but merged into its surroundings, the dust and grime rising from the surrounding yards and the smoke rolling out of the chimney fading the letters to a dirty grey. Half a mile away, hidden behind the sombre sheets of rain, the railway trucks and wagons of the marshalling yards set up a continuous metallic clank as they were pushed and shuffled from siding to siding. Visitors to the house would always mention the sound of the trains, but he had lived here for so long that Reg hardly noticed it. He let the net drop back and turned to the mirror to finish shaving around his neck. Perhaps it was high time he moved out of this terrace, he thought. But with Doris? A knot of guilt tightened in his stomach.

By 7.45 am he had completed the shaving and had removed a clean, folded shirt from the drawer. It would last him for two days – until Wednesday at least – but the separate collar pulled from a different drawer would be fresh every day. Fixing the stud into the back of the collar and then onto the shirt, he pulled his work tie from the rack on the back of the cupboard door. He was proud of his expertise in tying a Windsor knot – a skill he had learnt from a fellow soldier when he was billeted in Germany. Standing in front of the full-length mirror, he performed the tying

ritual before admiring the symmetrically triangular knot that sat perfectly central to his collar. For Reg, knots were important.

By 7.55 am he had put on his waistcoat and fixed the half hunter watch and chain from one buttonhole to the pocket on the left of his belly. The watch had been given to him by his father on his first day of work when he was fifteen and it had kept time flawlessly for thirty-seven years. Giving the stem a gentle twist with his fingers, he wound the mechanism carefully to its fullest capacity before automatically flicking open the glass cover and clicking it shut before slipping it into his waistcoat pocket.

He reached the foot of the stairs by 7.58 am and halted by the wall mirror to ensure all was as it should be. His suit jacket, as always, was on a hanger on the side of the hall stand. His hat and overcoat hung to one side and the work brief-case leant against the foot. Reg smoothed the waistcoat lapels and gave the lower edge a quick tug down. “I wish you were my Gary Cooper” his wife had said when they walked back from the pictures after a showing of High Noon the week before. It had been a simple phrase and one that he was sure Doris hadn’t thought about before she said it – a kind of back-handed criticism – but the memory of it still rankled. Once more he checked his tie, brushed his hair back with his hand and turned his face left and right to ensure he hadn’t missed anything when shaving. His moustache curved gracefully in a thin line from the nostrils to the corners of his mouth, elegantly equidistant, and the shallow dimple in his chin nicely set off his full lips. Satisfied, he turned towards the kitchen from where he could hear the pips of the 8 o’clock news on the radio.

There was something wrong. Reg prided himself on his sensibility and he recognized an indefinably strained atmosphere as soon as he entered the kitchen. Doris had her back to him, standing by the stove, skillfully spooning the hot fat over the eggs in the frying pan so that they didn’t burn at the edges.

“Alright, love?”

“Post’s there.” Doris announced with a marked indifference and without turning away from the stove.

Reg looked towards the small kitchen table that they used for breakfast and which Doris laid out each morning, carefully placing the mats, knives and forks opposite each other with the sauce, pepper and salt sitting in the middle. A cup of tea was already steaming by his plate. Against the sauce bottle leant a single brown envelope with the words On Her Majesty’s Service in black above his own address. Even from that distance Reg had a fair idea what it was and he guessed that Doris knew as well. That would certainly account for her frostiness. Reg sat down at his place and picked up the envelope. Postmarked: London SW. Picking up his knife, Reg slipped it under the glued flap at the rear and slit it open. Pulling out various sheets of paper, he unfolded them and read the covering letter.

Henry Charles Eastman

I have a condemned prisoner, named above, in my custody and you have been recommended to me by the Prison Commissioners for employment as Chief Executioner. Two copies are enclosed of the Memorandum of Conditions to which the person acting as Chief Executioner is required to conform, and if you are willing to act as Chief Executioner I should be glad if you would sign and return one copy of the Memorandum in the enclosed stamped addressed envelope. I would be obliged if you would treat the matter as urgent.

It was signed by the governor of Wandsworth Prison. A railway travel warrant was also enclosed together with a note giving the date of the execution: Tuesday May 26th 1953. Reg leaned towards a small shelf that held Doris’s recipe books and cuttings and pulled out a slim diary. Leafing through the pages he checked May 26th and found the date empty. Just over two weeks’ time.

Doris turned away from the stove, a plate in each hand. She brought breakfast over to the table and placed one plate down in front of her husband, deliberately covering the rail warrant and return envelope.

“Doris, love!” Reg extracted the pieces of paper from under the plate and folded them into the diary. Doris sat opposite and picked up her knife and fork. The curlers that she kept in her fringe overnight had been removed and the hair rolled over her forehead like angry waves breaking on a beach.

“I thought you promised me you were going to get out of this business.” She waved her fork towards the diary that lay beside Reg’s plate. “You know how much I dislike it.” She put her elbow on the table and pointed directly at her husband with the knife. “And if the company ever gets a whiff of what you do on your ‘little holidays’, as you call them, you can wave goodbye to your position there.”

“No-one knows, love. Never will.” Reg knew he was on tricky ground whenever the subject came up. Although he had promised her that he would hand in his resignation after the last job, he had found it difficult to make the final break.

“It’s not the kind of thing someone in your position should be involved with.” She cut into her egg, the soft yolk spilling over the lightly browned toast, her elbows jerking as she cut and folded food onto the fork. “It’s a job for the likes of publicans and bookies. You know who I mean.”

Reg knew exactly who she meant. Albert Pierrepoint.

Reg had remained in Germany after the war had ended, becoming involved with the organization of the Nuremburg trials. Pierrepoint, Britain’s Chief Executioner, had been flying backwards and forwards from England, hanging the condemned as the verdicts were handed down, but in the later stages he had found the intensity of the work exhausting. He had asked for a competent assistant from the army staff stationed at the barracks, and Reg had volunteered. He surprised himself on how quickly he had picked up what was required. Pierrepoint’s professionalism and emotional detachment from the task greatly impressed Reg and, in turn, Pierrepoint was grateful for someone who followed his instructions to the letter. Equally in awe of the speed with which Pierrepoint dispatched those condemned to death and touched by the respect he had shown the corpses after they were removed from the rope, Reg found himself fascinated by the procedure. Over a period of a few weeks an unspoken bond had grown between the two men and on one visit to Germany Pierrepoint asked Reg if he had ever thought about taking up the post of Assistant Executioner when he got back to England.

“It takes a special person to do this task, Reg, and I reckon you’ve got what it takes. A few times a year, that’s all. Won’t interfere with your day job and if you want a recommendation from me you only have to ask.”

Reg had indeed thought about it for a while and when he was finally demobbed he contacted Pierrepoint to see if he would support his application to be an Assistant Public Executioner. It was only after the application was successfully completed that he told his wife. He hadn’t meant to keep it a secret from her but the war years had driven an unspoken wedge between them and his experiences at the relief of Belsen in April 1945 had marked a sea change in Reg that he was reluctant to acknowledge to himself, let alone to his wife.

After assisting in about twenty executions between 1947 and 1951, Reg was finally given his own post as Chief Executioner and the job that he had just been requested to officiate at would be his eighth in charge; but now Doris was becoming increasingly vocal in her opposition. His job at the steel works had become more important as the post-war industry picked up and a recent takeover of a smaller steel outfit by the company had seen Reg rise up the hierarchy. He was close to acquiring the position of senior accountant and Doris fretted constantly about his “dirty little secret” – as she called it – being made public. Months of chipping away at him had finally made him promise to put in his resignation. A promise he hadn’t kept.

“I’m warning you, Reg. This will get out and then we’re finished around here.” Doris held her cup of tea in both hands and looked at her husband over the rim. “I mean it. No company wants a hangman as their chief accountant. They’ll lose business, and what’s worse, you’ll lose your job.” She put her cup back on the saucer with a clunk and a splash of tea fell onto the table’s Formica surface. She wiped at it angrily with the cuff of her dressing gown. “The next thing you’ll kno

w is we’ll have the papers round here, sticking their nose in, just like they did with Pierrepoint. It’s got to stop, Reg. I’m serious.” She snatched a piece of toast from the rack which Reg noticed was burnt, bearing the tell-tale signs of a knife scraped across the surface.

He leant over and placed his hand on hers but she pulled away.

“Promise me, Reg! This has to be the last time.” She looked directly at him, one eyebrow slightly raised. Reg recognized the signs.

“OK, love. I promise. I would have done it after the last but I was so busy at work I just forgot.” He withdrew his hand and picked a piece of toast from the rack, smearing it with some dripping from the pot. “Look, tell you what we’ll do. Why don’t you write out the letter of resignation for me and I’ll sign it and post it straight after May 26th.” He tapped the diary. “That’s the date for this one. Last one, I promise, love, the very last.”

Bradford on Avon, Wiltshire. 1939

Henry Eastman

“Eastman by name, sweetman by profession.” It was a favoured and much repeated aphorism of Arthur Eastman who ran the confectionery shop half-way up Silver Street in Bradford on Avon. The shop sat on a bend in the road and the windows were so placed that Arthur could look down towards the town centre and up towards the Manor House. The business had been in the family for nearly thirty years by the time Arthur’s wife, Mavis, gave birth to their son, Henry, in 1928. Although Arthur would have preferred a sibling for Henry, Mavis’s labour, stretching over some twenty hours and ending in the doctor wielding the forceps to grip Henry’s head and pull him down and out into the world, had been far too traumatic an experience to risk a second time. As Mavis sweated and grunted and pushed ineffectively, she had recurring visions of the vet on her father’s farm pulling the calf from its mother, the rope tied around its feet, before it slithered out into the straw. In Arthur’s terse opinion – but never given within his wife’s earshot – she “had shut up shop”. Henry was to remain their only child.

A Coin for the Hangman

A Coin for the Hangman